PARS

Some of Prime Time's staff have completed the Master Classes on PARS and we are developing our practice all the time!! Find out some more about PARS....

PARS is an alternative approach to working with children in their leisure time. Based on the practice of the UK adventure playground pioneers, the PARS model of playwork practice was developed from research by Dr Shelly Newstead and is now used by professionals (and increasingly parents) all over the world. PARS empowers adults to enable children to make their own choices about how they spend their free time. Research has found that PARS practitioners are less likely to intervene in children’s self-directed activities and are more open to children’s risk-taking behaviours, which increases children’s social and emotional development and resilience (Chan et al, 2020).

Historical research by Dr Shelly Newstead found that the practice of playwork was originally invented to compensate children for the presence of adults on adventure playgrounds (basically allowing children to play without adults interfering).

Grounded in the original philosophy of the adventure playground pioneers, the PARS model enables practitioners working in any setting to make decisions about whether and how to compensate children for the presence of adults in their time and space. PARS playwork practice is an ideal response for practitioners working in supervised settings who are concerned about shrinking childhoods and the loss of children’s freedom.

Playwork Principles are:

- All children and young people need to play. The impulse to play is innate. Play is a biological, psychological and social necessity, and is fundamental to the healthy development and well-being of individuals and communities.

- Play is a process that is freely chosen, personally directed and intrinsically motivated. That is, children and young people determine and control the content and intent of their play, by following their own instincts, ideas and interests, in their own way for their own reasons.

- The prime focus and essence of playwork is to support and facilitate the play process and this should inform the development of play policy, strategy, training and education.

- For playworkers, the play process takes precedence and playworkers act as advocates for play when engaging with adult led agendas.

- The role of the playworker is to support all children and young people in the creation of a space in which they can play.

- The playworker’s response to children and young people playing is based on a sound up to date knowledge of the play process, and reflective practice.

- Playworkers recognise their own impact on the play space and also the impact of children and young people.

- Playworkers choose an intervention style that enables children and young people to extend their play. All playworker intervention must balance risk with the developmental benefit and well-being of children

Play Types

Symbolic play

Play which allows control, gradual exploration and increased understanding, without the risk of being out of one's depth. For example using a piece of wood to symbolise a person, or a piece of string to symbolise a wedding ring.

Rough and tumble play

Close encounter play which is less to do with fighting and more to do with touching, tickling, gauging relative strength, discovering physical flexibility and the exhilaration of display. For example playful fighting, wrestling and chasing where the children involved are obviously unhurt and giving every indication that they are enjoying themselves.

Socio-dramatic play

The enactment of real and potential experiences of an intense personal, social, domestic or interpersonal nature. For example playing at house, going to the shops, being mothers and fathers, organising a meal or even having a row.

Social play

Play during which the rules and criteria for social engagement and interaction can be revealed, explored and amended. For example, any social or interactive situation which contains an expectation on all parties that they will abide by the rules or protocols, i.e. games, conversations, making something together.

Creative play

Play which allows a new response, the transformation of information, awareness of new connections, with an element of surprise. For example enjoying creation with a range of materials and tools for its own sake.

Communication play

Play using words, nuances or gestures for example mime, jokes, play acting, mickey taking, singing, debate, poetry.

Dramatic play

Play which dramatizes events in which the child is not a direct participator. For example presentation of a TV show, an event on the street, a religious or festive event, even a funeral.

Deep play

Play which allows the child to encounter risky or even potentially life threatening experiences, to develop survival skills and conquer fear. For example leaping onto an aerial runway, riding a bike on a

parapet, balancing on a high beam.

Exploratory play

Play to access factual information consisting of manipulative behaviours such as handling, throwing, banging or mouthing objects. For example engaging with an object or area and, either by manipulation or movement, assessing its properties, possibilities and content, such as stacking bricks.

Fantasy play

Play, which rearranges the world in the child's way, a way which is unlikely to occur. For example playing at being a pilot flying around the world or the owner of an expensive car.

Imaginative play

Play where the conventional rules, which govern the physical world, do not apply. For example imagining you are, or pretending to be, a tree or ship, or patting a dog which isn't there.

Locomotor play

Movement in any and every direction for its own sake. For example chase, tag, hide and seek, tree climbing.

Object play

Play which uses infinite and interesting sequences of hand-eye manipulations and movements. For example examination and novel use of any object e.g. cloth, paintbrush, cup.

Role play

Play exploring ways of being, although not normally of an intense personal, social, domestic or interpersonal nature. For example brushing with a broom, dialling with a telephone, driving a car.

Mastery play

Control of the physical and affective ingredients of the environments. For example digging holes, changing the course of streams, constructing shelters, building fires.

Recapitulative play

Play which rehearses skills for survival – not only for individual survival but also the survival of the human race.

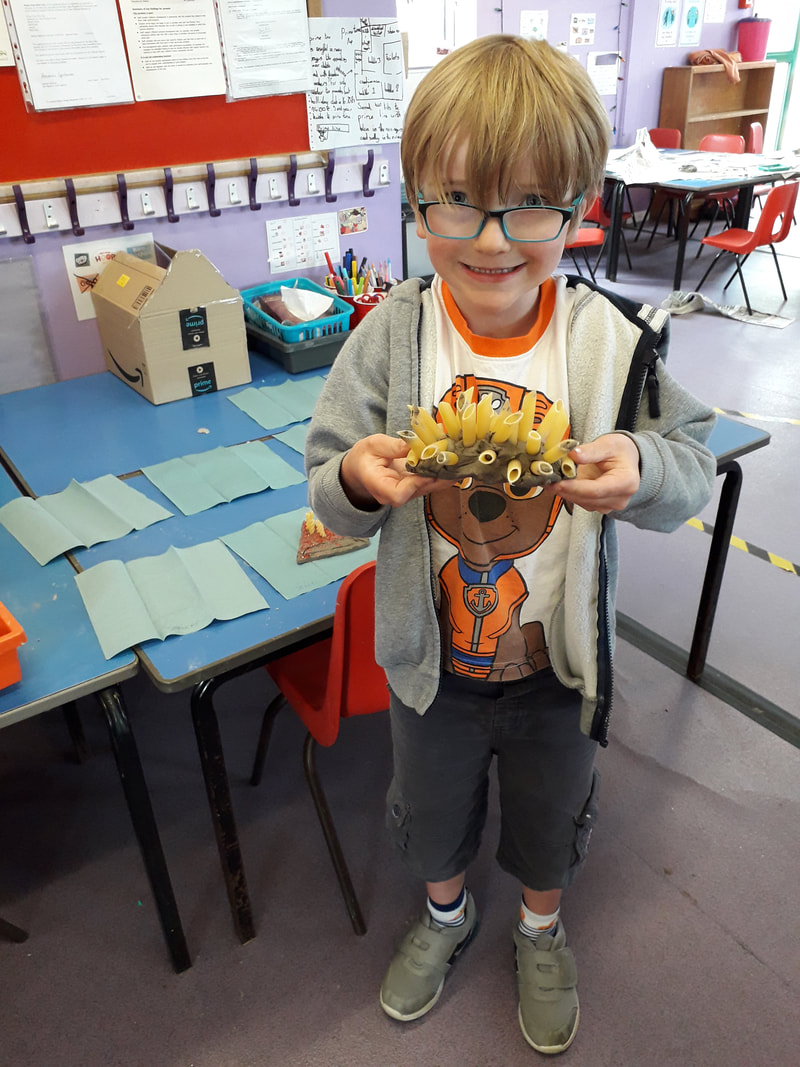

Loose Parts Play

The famous landscape architect Simon Nicholson in 1971 wrote a paper on ‘How to NOT cheat children – the theory of loose part’. Nicholson believed that it is the 'loose parts' in our environment that will empower our creativity.This theory has had a large impact/influence on the way play professionals and play space designers think today.

In his paper he stressed that children need opportunities to alter and change their play spaces and how a lack of participation of children in the design of their own environment can have an unstimulating play experience.

Loose parts play should

- Allow children to control and lead play opportunities – supported by playworkers

- Provide an environment which encourages children to use materials and resources as they choose to.

- It should encourage children to use their creativity, imagination and stimulate children to allow them to develop their own ideas and explore the world at their own pace.

What is a loose part?

Wood, tyres, logs, sticks, sand, shells, gravel, buttons, fabrics, crates, boxes, ropes, stones, fir cones and anything loose... "one mans junk is another mans treasure"